“All you have to be by the time you’re 23 is yourself.”

Themes at the scale of a generation

There is a podcast I love called Decoder Ring. The show explores “cultural mysteries”. The last episode I listened to was called “Selling Out.” It proposed that the concept of selling out was the overriding theme of Generation X.

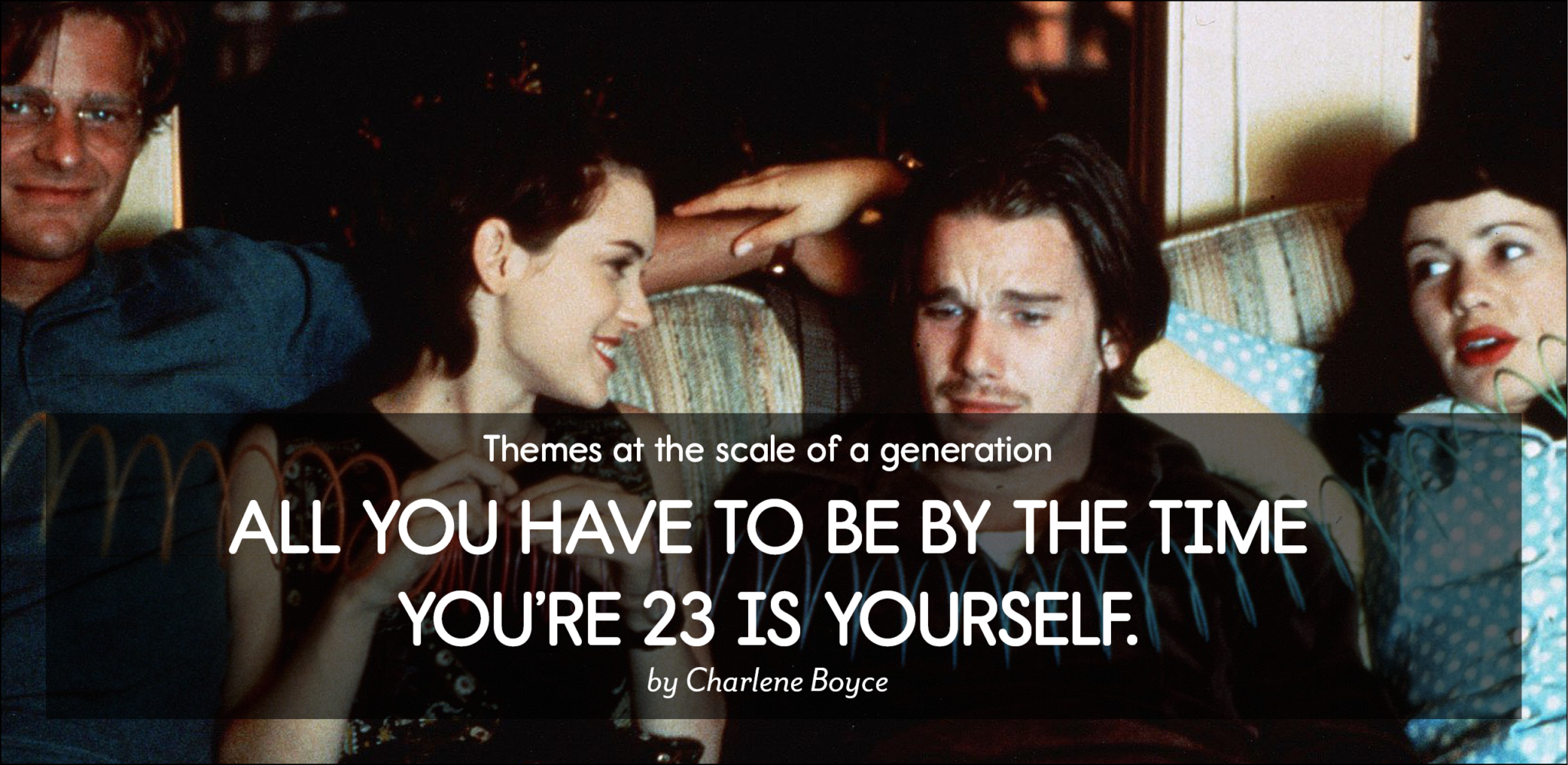

The podcast started with the story of the woman who wrote Reality Bites, the movie about Gen Xers coming of age. I remember seeing it in a theatre in Truro when it came out. I felt as I watched it that I had missed a boat — it was already too late for me (a seasoned 24 year-old) to embrace or be influenced by any of the motivational messaging in it. Note: Winona Ryder and Ethan Hawke’s characters were almost exactly my age.

I have always felt a little out of my own time. I resist being defined by that ‘generational’ analysis that divides us into 15-20 year birth cohorts, although I relate to Gen X memes. My dad’s birth year, 1925, in some reckonings qualified him as The Greatest Generation, while my mom (1928) was a Silent Generation member (although she was anything but silent). My three older siblings are straight up Baby Boomers. So I was raised with a foot in many generational cohorts, surrounded by cultural references I had no business knowing about: the Farkle family, Mortimer Snerd, Mrs. McGillicuddy. The concept of zeitgeist, or the spirit of an age, has long fascinated me.

But back to the podcast.

First of all, it is very gratifying for a Gen X to be seen at all, so thank you, Willa Paskin.

Second of all… wait, is this true? Has ‘not selling out’ as a generational theme affected my life?

If exploring intergenerational change intrigues you, especially intersectional intergenerational change, check out the work of the Nova Scotia Network for Social Change. They have an event coming up on SEPTEMBER 28, 2021 that may interest you, Voices from Community: The Unspoken Connections Between Mental Health & Aging. RSVP now!

My career has not followed a neat trajectory, but whose does? Especially people born 1965-1979, who experienced the same ripples in North American economies, and workplaces already full of Baby Boomers. At my first ‘city job’ as a designer at Speedy Print, the production manager told me that my generation really got the worst deal. She (about 15 years older) had walked out of high school and been fought over by employers.

HIGH SCHOOL. Imagine that. (I couldn’t.)

About ten years ago, I recognized I needed a narrative through-line to make my resume make sense. Although every step had made sense to me at the time and felt intentional, it looked like I had meandered, following random-seeming opportunities and interests. I have always followed my values, and this is how I made sense of the journey.

There was a point in my life where I was looking for a more lucrative job, in part because I was perilously near bankruptcy.

Several good-paying jobs were posted with the oil and gas industry. There was always the option of the giant insurance companies or the power company. I was shortlisted for, and then offered, a job with the Chamber of Commerce.

I gagged. I couldn’t do it. It didn’t line up with what I believed. It would be selling out, or so it felt.

So not selling out may indeed be in our generational value set. But did my values do anything to actually change the world in those choices?

There are some who would argue that working from the inside the system is the best way to make change. For instance, maybe working for the Chamber would have given me a small iota of influence that could have shifted some of their focus to social enterprises and cooperatives. Maybe? But probably not.

In truth, shifting narratives like “business is just about profit” or “capitalism is the only way to organize our economy” takes the combined efforts of large numbers of people, pushing at all the edges, individually and collectively. Every generation matters in this movement.

When you have generational cohorts all experiencing the same external influences (think climate change, global pandemics, wars, and so on), that shapes the zeitgeist. Boomers believed they would and could change the world (and they definitely did). Many Gen Xers believed that we just needed to survive, preferably with our values intact. Trying too hard wouldn’t make that much of a change.

The key is to tackle systems change intergenerationally: to leverage the resources and experience of the older generations, and the energy, attitude and assurance of the younger generations. (Of course, this assignment of “older” and “younger” is from my point of view, a Gen X with three generations in my immediate family, whose husband and daughter apparently both qualify as millennials.)

Maybe the generations that follow us, the Millennials and Gen Z and Alphas, will compile the generational lessons. So far, the indications are that they understand they can change the world and remain true to their values.

Here’s hoping we have left the next generations enough resources and runway to fix things.

Coda: I recently re-watched Reality Bites. It holds up, and with the perspective of nearly 30 years (I gagged a little as I typed that) I can recognize some of the conflicts I experienced played out on the screen. Creative smart woman proves unemployable? Hello!

Winona Ryder’s character projects her values and path choices externally onto the two men who are vying for her affection: the educated, disaffected, emotionally unavailable musician and the culturally clueless, emotionally vapid, ambitious business guy. In this rewatch, the “not selling out” idea for me personally was subsumed in the feminist read of the movie… even as late as 1994, the answer for an intelligent woman was ‘choose the right man’.

Thank heavens for Janeane Garofolo’s promiscuous Gap manager.

Share this:

Comments are closed