Governance, Leadership and Equity in the Sector

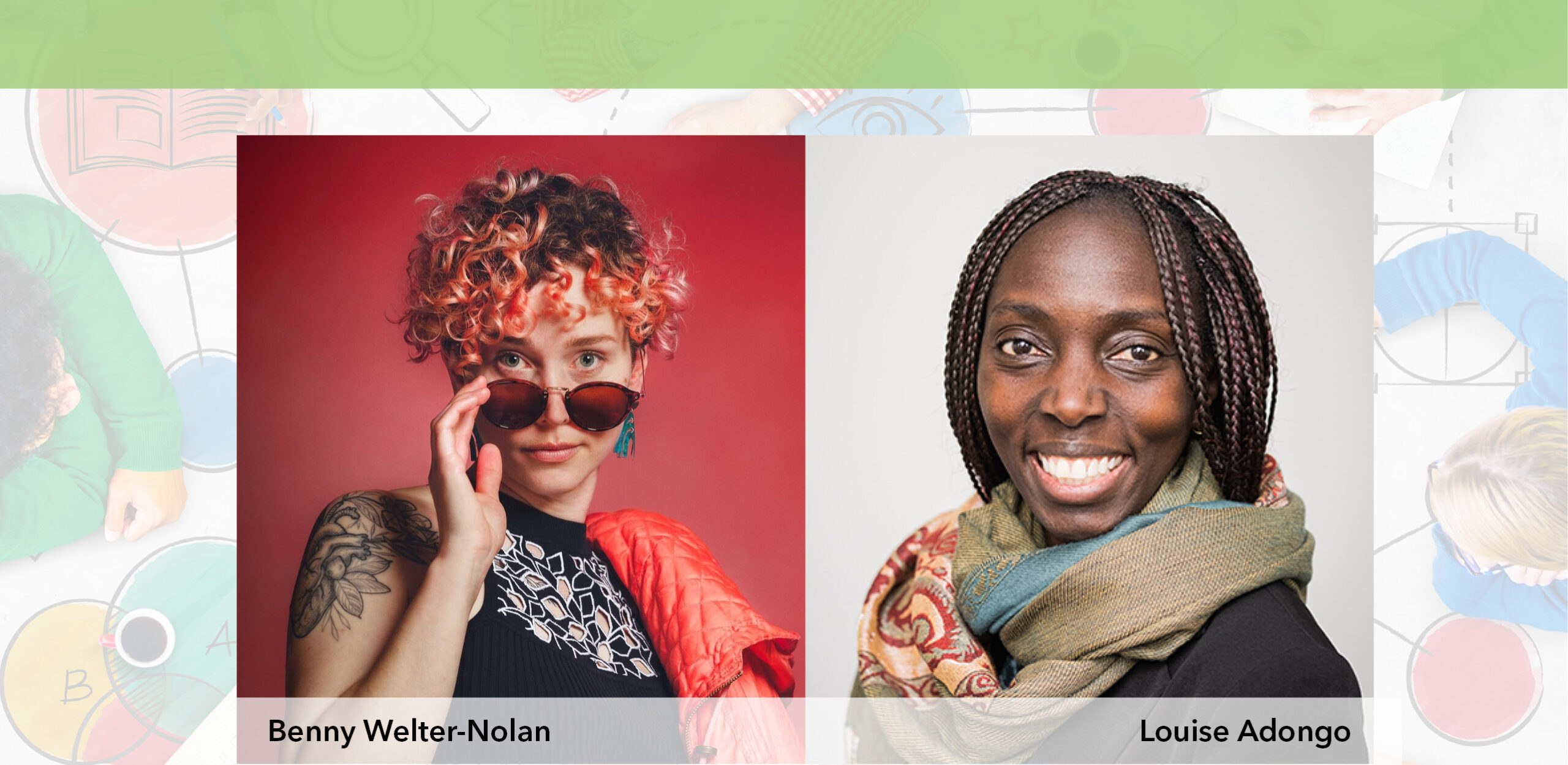

We opened this blog series with the intention to capture some of the thoughts and learnings about identity, intersectionality, leadership, equity in leadership, and burnout that Louise Adongo has seen emerge during her two-plus years with Inspiring Communities. She is joined in discussion with Benny Welter-Nolan, a consultant and strategic advisor who brings their own experiences in the sector. These are the reflections and lessons that they aimed to capture in this three-part blog series:

- Burnout is a systemic issue with individualized impact which is exacerbated for BIPOC leaders of intersectional identity.

Louise and Benny discussed this in their first post, Burnout and Systemic Barriers to Resilience. They noted that the burnout and trauma associated with leadership in this sector are endemic, and stem in part from the small, tight-knit pool of people associated; colonial, hierarchical structures inherited from government, funders and the earliest history of charities; and from the perception of one leader being accountable both ‘up’ and ‘down’, to funders, boards, communities and staff. In effect, leaders are the pinch point in the hourglass.

At the same time, expectations of funders, boards and others mean that the norms of executive employment are not present: salary, raises, and rest periods require extraordinary measures to achieve. In the past, holders of these positions usually had financial, class and social personal support systems that a new generation of leaders often don’t. All of these challenges are then multiplied when a leader is a member of a BIPOC community (see https://nonprofitquarterly.org/the-perils-of-black-leadership/. Often these leaders are hired into a situation of complex challenges and wear the pressure of resolving these. - Healthy transitions and succession are vital to leadership retention and impact.

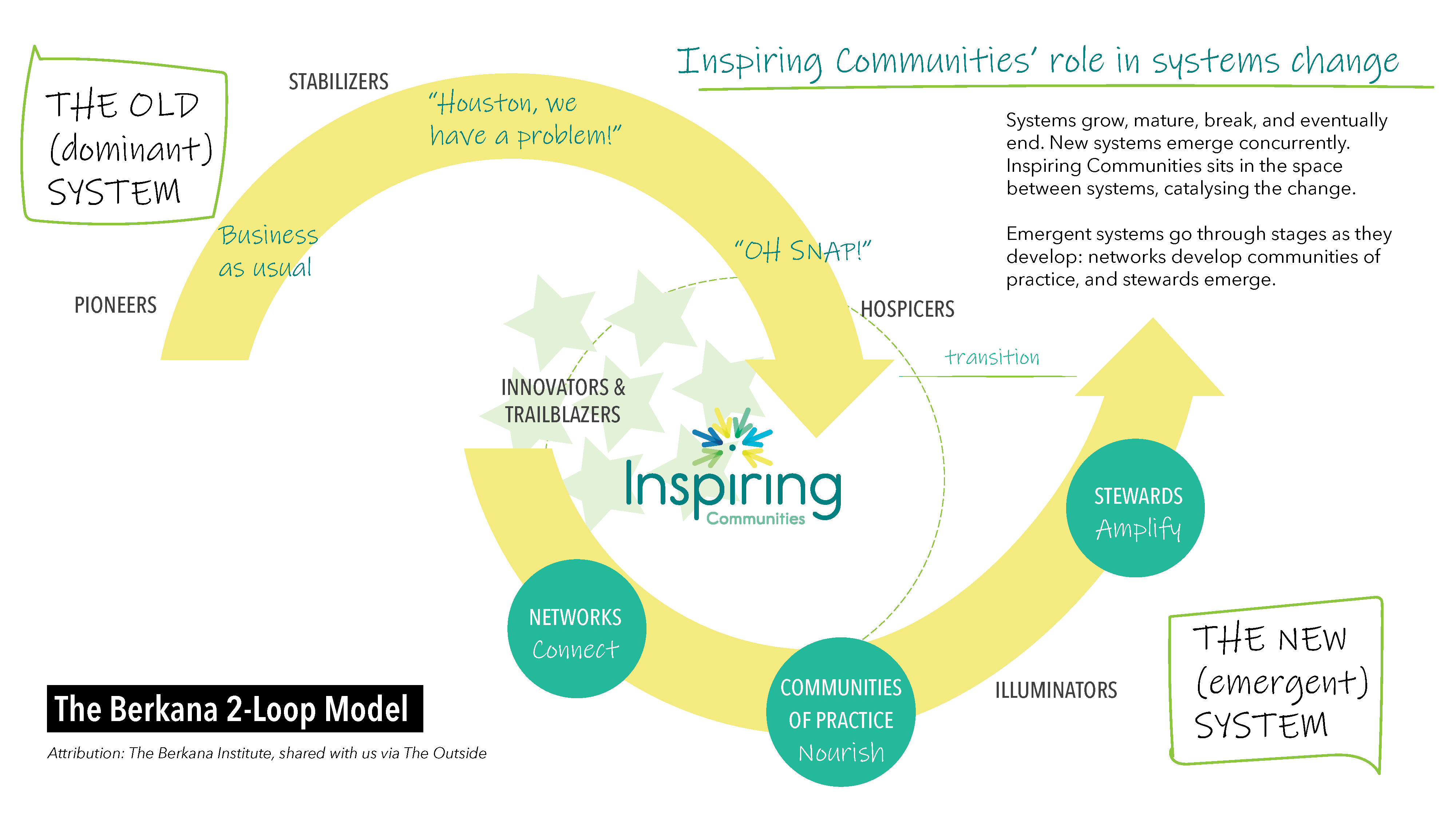

In the second post, Collaborative Leadership as a Model for Healthy Transitions & Succession Planning, Louise and Benny explored the ways leadership, governance and funding affect the ability of an impact organization to explore alternate structural models. Traditional funding models, for instance, rarely fully support administration funding, which maintains the organization, human resources and processes that enable the work. They mentioned innovative approaches to financing (mission-driven financing, trust-based philanthropy, arms-length managed funds) that show promises of changing this dynamic.

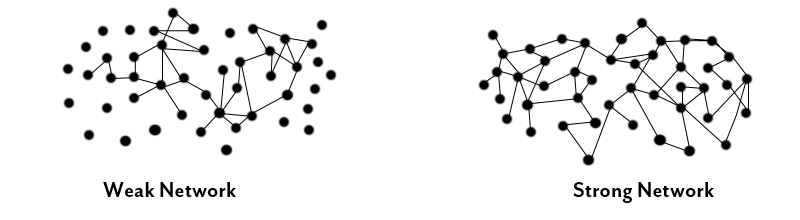

The not-for-profit industrial complex, including tax structures, maintains a competitive system that does not serve the work. Co-leadership is an interesting alternative model, but also requires pushing into regenerative governance structures – think of the resilience of mycelium networks.

- Co-leadership is an opportunity for systemic change to support plurality, particularly in the context of systems transformation and equity work. Read on for an inspiring vision of how collaborative co-leadership and regenerative board structures can begin to transition us to a better system.

Collaborative Governance

The way I have come to understand collaborative governance is through the webinars Tamarack has co-hosted with Inspiring Communities New Zealand on re-imagining and evolving collaborative governance as well as the networked governance model used by the New Brunswick Social Policy Research Network. The challenge I’ve considered in these models is that they involve people, and humans are consistent in our patterns and mental models, which impact our behaviours and how we’re working together. If people are generative, open, creative, amenable, and have a bond, that works really well. Sometimes the most traditional-looking boards are able to do the most innovative things, and so I guess I need to understand what different approaches and types of collaborative governance models are out there before I consider it. How do we manage the power dynamics?

Governance is so important to me because it lays the foundation for how we work together and organize ourselves. It can seem hard and annoying because it engages in and creates bureaucracy within organizations and most of us get frustrated by bureaucracy. My passion for this work started when I was growing up, my public school had a Model United Nations program that took students to debate at the Hague. I didn’t grow up with a lot of means and had to take an extra semester at school so I could save enough money waitressing to participate. I really wanted to understand how to make a difference and thought international policy development might have the biggest impact.

It was really an eye-opening experience. There was a dress code, you had to wear a suit, and there I am in my mom’s business suit from the late 70s with a real nine-to-five aesthetic, in a crowd of mostly private school students from all over Europe. What I learned in that experience was that international policy development isn’t very effective, and that it is largely governed by the wealthy elite.

That’s when I decided to pursue the arts and community organizing because culture is what changes hearts and minds – that’s what you need to change before you can change public policy. We need radical imagination to question how our systems and structures function and imagine different ways of relating to each other. Governance codifies the nature of our relationships and the systems we’ve devised to collaborate. In order to organize effectively we need to be very thoughtful about how we are collaborating with each other, and undermine the governance norms we’ve inherited from European colonizers and enforced through Canadian charity regulations.

Equity, Locality and Language

As I was listening to you, I thought about the book Elite Capture talking about the inner workings of government. In the history of governance and civics, people were best served when multiple perspectives were being considered. And then somehow the elites within governments convinced others that there is a singular best course of action and that there is no knowing that is collective. The book talks about how the tools of collectivism have been captured by the elites that claim to have more expertise than the communities they serve.

It also reminds me of someone I know who retired from the government many years ago. I asked what helped them make the decision to retire, and they said “it felt like other people were not allowed to know things. It’s a kind of culture where only certain people are allowed to know things.

In the introductory Arantzazulab blog, Michelle Zucker’s research into transforming ecosystems, she theorized that burnout is the barrier to expanding new governance models to have a global impact. But I think more than that, the globalization of systems change doesn’t accommodate for the challenges of a specific region. Thinking about your reference to Elite Capture, it seems like we’re continuing to engage in a colonial mindset that there is a universal best practice that must be adopted globally.

What makes more sense to me is having networks of information exchange, giving local organizers resources or building partnerships where there is a common cause or alignment. I cannot stress enough the importance of community level implementation. Every circumstance has its unique challenges and the people directly involved have the best understanding of what they need. Working in a provincial service organization has helped me understand that each community has different needs, even in a very small province like Nova Scotia. Regional perspectives actually have a big impact on the success of a project. I do see that exchange of ideas, tactics, research and networks is very important in learning about new methodologies that could be of use to a specific locale, but I find it difficult to imagine that systems change implementation globally wouldn’t be a kind of elite neo-colonization.

Thinking about implementation and impact, it can be really difficult to predict the outcomes of new governance models. This is a common challenge for artists accessing funding as well – people are expected to outline the artistic deliverables in advance of testing the process. In both cases, if you’re focused on the outcome and not the process, you can create a lot of dysfunction. Funders typically need to have a proof of concept or effectiveness, research that substantiates the work. Even in this blog series we’ve both been concerned with having to prove our own lived experience. I think sometimes lived experience is challenged because we put so much of the responsibility onto the individual to succeed: unless we’re able to identify some kind of statistical demographic trend, people would rather assume an individual’s inadequacy than systemic oppression. Even when it aligns with a broader narrative, our own individual experiences are likely to be scrutinized.

I think about how colonizers divided knowledge, separating the sciences from the humanities, with science being the *truthier* understanding of reality. But I think there is a common curiosity between artists and scientists, and that’s a beginner’s mind. What is the question that hasn’t been asked yet? If this isn’t working, what is another methodology? In the context of governance, if we are only concerned with outcomes and not the process, we will continue repeating harmful patterns. I think there is a potential for healthier relationship dynamics if we collectively negotiate how we work together to improve conditions for everyone.

I’m seeing how community organizing gets stalled because of perfectionism. In Michelle Zucker’s research she also highlights how language has been a challenge because themes are very much related, but individuals have very particular language to give specific nuance to their concerns. I see this often in 2SLGBTQIA+ communities, where the very important nuance of these identities can create barriers instead of building solidarity. I don’t often feel comfortable attending women and non-binary closed space events because I know there to be many Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists (TERFs) in these communities.

I think there’s both people saying the same things with different language, and people using the same words but with different meanings. And so …this is something to be mindful of – how when we’re talking about governance, we’re not just talking about boards, we’re also talking about how we’re working together in and between organizations.

The manner in which governance is enacted upon the social purpose sector has not caught up with its needs. I don’t even know if there is a mechanism for extracting ourselves out of these instruments of governance that have been used to suppress the social purpose sector instead of creating an enabling environment. When the laws changed to allow charities to engage in advocacy just in the last few years, that was a huge deal. When the rules of one governance structure bleed into becoming norms across the ecosystem, we need to interrupt our assumptions.

Exploring Alternatives

I think this is why it’s so important to have people in governance that ask why are we doing things this way? Is this actually a law, or is it a norm we’ve adopted as a shorthand? That kind of curiosity creates change. Changing our foundational governance models from colonial and capitalist approaches is a huge challenge because we are changing the cultural norms of our relationship agreements in a professional context. It’s going to take years for people to adopt those changes on an individual and social level. It’s challenging and necessary because the norms we have been engaging in no longer serve us and are actively hurting so many in the social purpose sector.

The norms of how we have been engaging with each other are broken. Other forms of organizing ourselves have existed for a long time but they have been dismissed and discouraged by colonial bureaucracies. Even to outline a few different ways to structure ourselves as an organization and provide leadership is hard. Outlining how accountability is held, who is responsible for what, and how information is shared, there is a multiplicity of approaches that could serve us better than our current norms.

What excited me about the Arantzazulab research is that someone took the time to review what alternatives exist, how are people working together differently, and how are people feeling in those structures? This work may be concluded for them, but how do we in the process of examining and creating collective governance, build systems in such a way that they are continuously co-created?

We can’t continue to operate as usual, it’s no longer helpful to do what we’ve always done, or replace one rigid system with another rigid system. How do we move to a place where things are good enough and people can continue to improve them over time? How might Registries of Joint Stocks across Canada create space for alternative possibilities through the templates for Articles of Incorporation, bylaws and other associated documents of the formation of societies.

We necessarily have to move from the systems we’re currently operating in. We might try to build something entirely new but it will be very difficult for people to adopt all at once, increasing the risk that the new strategy will collapse and invalidating the parts that could have been successful. We need to reflect on what hasn’t been working to pick out what’s no longer serving our collaborative efforts, and not overlook the parts that have been working well to bring us together.

Working with artists both creatively and within a governance context has helped me recognize that starting with a container to push against can be more constructive than a blank page. Often when we start “fresh” we recreate what we’re familiar with. But if you give creatives a box, I usually see them asking: What is this box for? How can I better use this box? Can I undermine its functioning as a box? What if I take this box apart and reconstruct it into another container?

We don’t have to start from the beginning, we can adapt over time to build more sustainable and human-centered systems of working together. Containers are really necessary in my opinion, because they help us understand the boundaries of how we are engaging with each other, and what that container’s purpose is.

I love that you just talked about the container. Moving from the word box to container is already generative because when you say box, everyone has the same cube image in their memory. And when you imagine a container, it can look like many different things and they all serve to hold different things. It becomes a mechanism to maintain integrity, accountability, and honour the supports you’ve been provided. We’re not saying we don’t need a container, we’re saying it doesn’t have to be a box.

And why are we replicating the containers and constraints of the corporate sector in the not-for-profit sector? Why are we adopting a corporate structure for something that is delivering entirely the opposite service? In fact their governance is arguably more flexible and board members are usually compensated for their contributions.

Expanding governance understanding and language

I think that’s also a part of the problem of our current board governance structure, especially when we are engaging people who are working outside of the not-for-profit sector and have more experience on corporate boards. The model feels familiar but the needs are entirely different. There’s an assumption that their sole responsibility is to attend meetings and offer guidance to staff. I need boards to understand that the needs of these organizations are greater and that at a minimum they must take on the responsibility of organizing and governing themselves, and championing the organization within their networks. It’s actually a good thing to have people leading your organization that are personally invested in its success.

I don’t think enough boards really understand their role as a leadership team meant to collaborate to elevate an organization’s impact. Too many boards rely on one or maybe three people if you’re lucky, to hold a dozen people’s work. Each member of a board of directors is leading the organization, not just the Chairperson. Each individual has an impact on the larger organization, even in their absence.

That’s why I think stakes are so important. Recruiting people that are impacted by your work to its highest level of authority, and having diverse perspectives in governance is really important because those people understand the impact of the decisions they are making and the consequences of inaction. Nothing about us without us should be a central focus of board recruitment.

Colonial governance models systemically barrier equity-deserving individuals from board leadership in many ways. I think first and foremost of alienating board members from the work an organization delivers through board hierarchy and the hourglass flow of responsibility through the Chairperson and Executive Director. We mentioned it in a previous post, but conflict of interest policies are also usually in direct conflict with a nothing about us without us approach. It also often bars us from developing relationships within the communities we serve to prevent a perceived conflict of interest.

There’s a group of lawyers that are working to decolonize conflict of interest and code of conduct policies from the perspective of the Truth and Reconciliation Calls to Action. I would love to see where that work has grown from an Indigenous lens: how are these policies harmful and how can they be different to better serve collective impact? Bringing an Indigenous lens to policy building could have such a huge impact on our relationships and could be regenerative for whole communities and consider the larger ecology. Limiting extractive relationship dynamics and creating mutually beneficial systems to bring more balance into our collaborations.

That reminds me I wanted to talk about language in the context of policy building, because we have really normalized using a language of colonial governance. When I worked at Saint Mary’s University Art Gallery, Ursula Johnson, an L’nu artist, taught me that Mi’kmaw language is entirely relationally based, and that you have to understand the nature of relations to communicate. English is a very object-and-action focused language that I think contributes to our widespread objectification and focus on property distinction and ownership in the West.

I think there’s so much to be learned from Indigenous languages and governance, especially considering how colonial governance has been used to control, oppress and subjugate on a global scale.

I also think this is why it’s so important to recruit folks from different perspectives, especially those who haven’t been on boards before. Sometimes they will notice aspects of the system that are painful that people who have worked in the system have normalized, and they can ask if this is really how we want to work together. This is another part of why lived experience is so valuable – everyone has a contribution to make even if it’s not a professional certification. I want everyone to understand that their contributions and perspectives are highly valued.

Organizations have been doing better at recruiting equity-deserving individuals to their board membership and into board leadership roles, but this doesn’t work if they are the only ones in the group. There is a risk that their perspectives could get drowned out, undervalued and ignored in service of majority votes. In some cases they burn out and leave because they experience harm in the position or feel silenced, unheard or that their expertise is not valued.

We’re also asking people not just to join a system that has oppressed them, but to uphold it. I think one way we address this and build more trust is by making sure everyone in leadership has clarity in their role, is valued for their contributions, and no one is working alone.

I see high functioning boards take succession very seriously and make sure each individual has a specific role. If they are not part of the executive committee, they are chairing a board committee, or if they are brand new to the board they are secretary, vice chair or co-chairing a committee to be mentored into the role next year. Each board member should have a responsibility beyond attending board meetings and each should be able to speak to part of what the organization is delivering on. Everyone is a part of the team and no one is working alone. Trust building is everyone’s responsibility in team leadership. If everyone has clear roles and responsibilities, trust building is made easier – everyone is working together and can demonstrate that they are responsible for their work, or communicative if they’re facing a challenge. When responsibilities are made transparent everyone understands each person’s contributions and the workload can be distributed more evenly across the board.

We also talked earlier about who has the privilege to sit on the board of non-profit or charitable organizations – people who can afford to volunteer and don’t need the income. For me, it’s not even about the financial compensation, although it does matter to be able to be compensated financially for your time, so much as mutuality and valuing someone’s contributions. This reinforces the barrier to participate as a board member in organizational leadership.

I’m glad you brought that up because I was thinking about highly effective boards I’ve worked with before and reflecting on what they do differently. One highly effective organization with a working board and no staff was producing craft fairs and I believe they were so effective because everyone had a vested interest in the success of the markets. No one on the board was compensated for their work, but they weren’t barred from selling at the fair which in some organizations would be considered a conflict of interest. But in this case everyone was very clear on their responsibilities and highly invested in delivering on them so the market was successful. The motivation becomes intrinsic instead of altruistic.

In most of our organizations the system bars us from this kind of benefit and when leaders are stretched, altruistic efforts can be de-prioritized because they are not directly affected by the success or failure of the organization. I think this system alienates us from the work being delivered and makes our individual impact unclear. I also think it’s okay to want to organize not just to strengthen our communities, but because we are part of that community too. What I’m seeing is the charity regulations systemically prevent us from bringing our whole selves to the boardroom table.

Moving away from “cult of personality” leadership

I also just wanted to say in the context of restructuring leadership, we really need to move away from these hierarchical systems where it entirely depends on the high functioning of one big personality. When the work and culture relies on one person’s vision, when they transition out or need time away, it can really destabilize the organization.

One of the reasons why I wanted to start this work was because I wanted to share what had been learned and built by many generations of people over forty years at an organization governed by the people it was built for. We can’t be reliant on a singular personality for holding the organization’s vision. It needs to be collective to be sustainable and everyone needs to be responsible for upholding and communicating the value of the work. These networks help keep the organization centered around the mission during transitions because it’s collectively understood.

I also think giving staff and board members the opportunity to collaborate on mission work together when the goals are clearly defined helps give leaders more context for the work and builds trust within the staff that they understand their circumstances. This way if one or more leaders leave, there is an understanding of the roles needed to be filled and the work can still be carried by the remaining members who are more involved.

Building these collaborative relationships is a huge trust building exercise. You have to trust that the committee Chairs understand their assignments, uphold the organization’s mission, and that they won’t overstep their role and start directing staff. It also gives other staff the opportunity to build trust with board members in case they are experiencing challenges with a new Executive Director and don’t feel safe bringing it up with their direct supervisor.

When the vision and goals of an organization are clearly defined, this expanded communication network holds the work regardless of one person’s absence and increases transparency. We also need to understand that if we’re not clear in our goals and directives, we will not be able to collaborate effectively. Sometimes it’s not that someone is unfaithful to the mission, it’s that we haven’t been detailed and transparent in our communication or we haven’t provided them the tools to help us effectively. That’s why we need thoughtful governance structures to be a reference point for how we are upholding our relationship contracts within the organization – when we are well supported by the container, we can focus on contributing our best work.

There’s absolutely enough work to go around. Enough change to be made by every single person. We need everybody to participate, we need everybody to show up and collaborate with each other because we cannot do these things by ourselves.

I think what can be really difficult for singular leaders is giving up control over the outcomes of other people’s work. Part of trust building is giving people the opportunity to help us meaningfully, with work that makes a difference to the organization. We also have to accept that people aren’t able to help us in the ways that we need unless we are clear with our mission, terms of reference, and onboarding. And even in that case we need to build in supports that accommodate for people’s individual interpretations, or unexpected absence. We need to be able to create a system that is flexible enough to hold people’s failures, because when people aren’t allowed to fail it has a huge impact on psychological safety and disengagement in an organization.

But when you’re the Executive Director who’s holding it all together, there’s not room for failure, and you can’t let anyone else fail either right? Because it directly impacts you, it feels impossible to trust a volunteer especially with a role, because their availability is limited and can be inconsistent. I think the transparency is a key element here. I’ve been a part of boards where there was no transparency of information and when they tried to implement a new governance model it failed because you couldn’t trust any of the information. My point is that if we’re making a networked web, we have to make sure we’re not spreading a virus.

I think we’re naturally conflict avoidant, especially in the impact sector because we are trying to avoid causing harm or further distress. But I want to share a quote in the context of transparency about generative conflict:

“When we avoid difficult conversation, we trade short term discomfort for long term dysfunction.”

– Peter Bromburg

I think the sector largely avoids difficult conversations and change because we want to avoid shame. If we are wrong we will be excluded, which keeps us from making changes unless they are “perfect.” I think perfection seeking in our work is a rampant white-supremacist presumption that stalls progress. Because language can be so limited and our circumstances are constantly evolving, we need to write policies and procedures that provide clarity and guidance while also being flexible enough to be adapted when new circumstances require new approaches. Letting everyone contribute their “good enough” moves us ahead, and we can trust our successors to make iterative changes when they need to. I think building abolitionist frameworks into our governance systems will help move our work ahead with less shame and more grace.

We are asking people to make foundational changes to their relational approaches. This is a generational shift and we are not going to solve all of our problems in a two or four year board or staff term. This work takes countless individuals making their best contributions, even if the impact won’t be seen in their time. So how can we create a container with a stronger base so the next team can be held more gently? When we’re turning over the soil, how are we picking out stones and adding nutrients for the seeds we plant to thrive?

I think that’s such a powerful way to end, and I think it is also a shared sense of responsibility and stakes through time. Reflecting on our leadership roles and how we are approaching our contributions: to stabilize or to fracture? There are things that absolutely need to be dismantled, and we need to imagine new possibilities. We are living in a maximalist culture, and I think people underestimate the impact of discontinuing something that’s no longer serving our purpose.

I think we’re turning a corner and recognizing that we must take some things away in order to make space for new things to grow.

Share this:

Comments are closed