Collaborative Leadership as a Model for Healthy Transitions & Succession Planning

In our last post, we joined Benny Welter-Nolan and Louise Adongo in conversation on their experiences of burnout. Review the introduction here and the first post, Burnout and the Systemic Barriers to Rest & Resilience, here. The conversation painted a vivid picture of the state of exhaustion and dispirited morale among leaders in the impact sector, particularly racialized leaders, or leaders from the 2SLGBTQIA+ community, or leaders with disabilities. Intersectional identities can further compound the problem. There is no question that leaders with diverse identities and backgrounds enrich and deepen our work. New models of leadership are required to support and sustain these leaders.

Healthy transitions and succession are integral to healthy organizations. There is a crucial balance between maintaining momentum and direction fueled by a singular shared vision, and injecting new ideas and innovation to continue to feed curiosity and sustain interest. How can nonprofit organizations maintain this balance, and in doing so, also make leadership positions more sustainable? Collective leadership is one model worth exploring.

Funding

It was great to start this off last time with our burnout journeys. And I know we have each gotten feedback from people reading our content and appreciating what we shared. It was not easy to talk about and it felt like we got to the very bottom of things and now we are on the way back up to daylight. Sort of an iteration of Otto Scharmer’s U. In our next two blogs I’m eager to start to move up the other side. I’m ready to talk about what we have each learned about alternatives though.

What I noticed in the last blog was that our conversation featured key themes around funding, leadership and governance. So I’d like to take each of them one by one and chat a bit about alternative models we have discovered for them. Did you notice any other theme?

I think it’s also worth talking about how our hierarchical models force us into conflict and competition with each other and that to build more collaborative, sustainable models, we need to find governance systems that support relationship building. How can we create the conditions for people to bring their full selves to these roles?

I think we need to capture this moment where people are recognizing that these systems aren’t working for anybody. If you want to create an environment that supports more people to survive and thrive in leadership roles, we need to be behaving differently and have new approaches to support.

Where this shows up for me most is interfacing with granting bodies and government funders. It’s one of the parts of leadership in the non-profit industrial complex where colonialism and oppression show up most obviously for me. I was reflecting to my colleague that this is one of the only parts of the work where institutional education has really served me to understand how to decode the language of funders and reflect back to them what they want to hear in order to gain their support for our work. Similar to debate, it’s not about whose argument is most ethical or constructive, but who is most convincing. And how you make it seem like their idea or point out the ways it is aligned with the funder’s goals, and how it’s going to make the funder look good.

Louise: Ok so it looks like you got us started with funding, so let’s get into it!

Well it’s a very imbalanced power dynamic where funders are offering resources but often aren’t engaged in any direct delivery. And because we rely on their support to deliver on our shared priorities, sometimes we’re not assertive enough about what we need in order to carry out our work. And our boundaries trying to balance direct delivery and often spending more time on the reporting requirements because of funder pressures.

And shaving off the truly innovative and radical parts of your project because you can’t upset the status quo.

I was part of a discussion last week about how to gain success in funding and what type of placemaking projects have usually been funded. The projects that see support are beautification and arts-based projects, when meaningful placemaking projects that invest socially in the people that live in these places are less successful.

We also talked about support for the “impact” projects, not core costs. But if we can’t pay rent for the space, or process the salary for the person delivering the project, or the prep work required to deliver the project, you can’t deliver on impact.

This conversation reminds me of private and corporate foundations only being willing to support high profile impact project delivery even though you often can only access $3000-5000 as an initial project investment. Then they also tend to get disappointed if the project didn’t go as planned. Meanwhile, they won’t provide support to the administration that creates the conditions for that project to succeed.

In the same way that we sent form letters to organizations posting jobs without a salary citing the barrier it creates for equity-deserving applicants, we started writing to funders who won’t support admin fees in their project funding because we can no longer afford to offer complimentary overhead to deliver on funder priorities. If you want us to provide an annual audit for your reporting, you need to at least provide us with some means of paying for an annual audit.

Louise: Yeah, we need to unpack this fantasy land that perhaps some funders live in about how work happens. I recently read reflections from a former grantmaker. Their perspective on all this was very illuminating and a lot of it mirrors what you are sharing.

And funders also dictate how we’re supposed to deliver on our mission or priorities without much familiarity about how we work with communities or what the needs are that we’ve heard from the people we serve. It’s so bizarre and totally normalized. We’ve all experienced funders asserting their power over organizations to serve the vision of a privileged institution. So much of philanthropy is derived from oppression. How come you have this money or generational wealth in the first place? I am very encouraged to see people asking themselves that question when making these applications.

Alternatives are emerging that are encouraging to see: Mission driven finance that flows capital to historically underinvested communities, also trust-based philanthropy.

The Peel region’s participatory grantmaking has gotten rave reviews; also the council of aunties that funders have to apply to in order to fund Indigenous groups is an interesting power shift.

Funders believing in the mission of an organization, offering multiple years of support and trusting the org understands how best to allocate those funds. And these shifts likely connect to what’s next, which is how leadership shifts and better integrates external perspectives (Christian Bason’s Mission Managers).

But first, what have you noticed that is encouraging around how funding is shifting for some, if not for others?

There is always a lot more work to be done, but I want to highlight the changes in cultural funding that have been really supportive to the sector. I think maybe this is because there’s a greater understanding that needs change rapidly and that failure is a part of the development process.

I feel like in our broader funding models there is no room for failure so instead of funders and partners learning from each other’s challenges, there’s a pressure to always report on success so that you’ll continue to receive support. When there’s no room to fail, it prevents us from trying new methods for solving old problems and we perpetuate the harmful systems out of a scarcity mindset. We don’t talk enough about risk and failure and allowing for more of it in the social purpose/ nonprofit/impact sector. We need to encourage more of this in our sector and appetite for it because how else are we going to seed and fertilize new models that are alternatives to what we know is not working?

Most government funding for the arts at this point has been moved to arms-length, where your peers are assessing funding requests instead of staff. This creates a bit of distance from government cultural engineering, but you still see that show up in the design of funding eligibility and criteria for support.

Arms-length arts councils are also able to set some of their own priorities governed by a board of artists instead of taking direction from elected officials or department CEOs. I see them reckoning with the same issues we are around equity-deserving representation, identity politics, and accessibility. I’m also really impressed by how receptive municipal and provincial funders were to the cultural sector’s advocacy efforts around core funding.

I’ve had some experiences with peer evaluation as progressive processes. Both Black Opportunity Fund and Foundation for Black Communities use this, and, as you’ve mentioned, arts-based peer juries.

And, what I find in these contexts is that it’s also a challenge to many in terms of conflict of interest policies in the interest of “objectivity” when the policy is counter to why we’re there in the first place. It is like the tools and instruments have not caught up to the progressive practices (speaking of governance changes needed).

I mean when you think of peer-review; it could be argued that part of the assessment by peers means we have connections, networks, and insights into these smaller communities. Our very ability to reflect on these in an assessment process puts us in conflict, depending on how strictly or loosely the conflict is defined.

I agree that we are all still operating within the confines of colonial bureaucracies and the tools and approaches need to change in order to undermine the barriers inherent in these systems.

I do like that some funders have started being transparent about how large a fund they have, how many projects are funded, and how many applicants they usually have. I remember attending a session Health Canada hosted where this was asked and answered. I think that level of transparency helps organizations manage their expectations and understand if it’s worth building a pitch.

I agree, it is very helpful for people to assess the likelihood of getting funded by probability. It is also extractive to have all these applications sitting unfunded and no one knows what happens to the ideas unexplored. What you are describing is similar to how not listing a salary in a job posting creates barriers for equity-deserving applicants. I think building funding transparency has the same effect as posting a salary. With HRM project funding for the arts I can see how many people last applied and who received grants, and I can also tell from the shared data that projects are usually only approved for 60-70% of their requests which changes how I build my projects. I know how I’m planning to pivot if we only get partial funding.

Changing Leadership

Ok so now we are going to talk about leadership. I know in the last blog we mostly talked about what’s not working. And I want to talk about alternatives we have each researched.

And then also, inspired by your identification of failure and our discomfort with it, I also think we need to give ourselves more permission and space to talk about how things are broken. People (including me) are very uncomfortable with naming what isn’t working and focus only on solutions. I think it’s important to reflect on what’s not working before immediately jumping to solutions that may not work because we don’t understand the scope of the problem. How do we make more conscious decisions about how we’re moving forward? I want to really encourage people to think about how not to perpetuate those systems. (*pauses emphatically and takes a deep breath – this sitting in stuff is uncomfortable.) So, Benny, how do we facilitate healthy transitions and support people, leaders in particular, because I think it’s bigger than burnout.

I’m so grateful to be working with Inspiring Communities to develop this work – it’s creating systems change because the systems that we’re working in have not been serving us. I want to help organizations build real solidarity and healthier relationships with each other so the work can move forward with more ease and collective support.

What I’m recognizing in the not-for-profit industrial complex is that we are using the same colonial systems and tools in our organizations that have caused many of the problems we’re trying to solve. The hierarchical governance structures that are embedded in our charitable registration with the Canada Revenue agency, puts us in immediate conflict with each other.

It especially puts equity-deserving leaders in a compromising position when they are trying to make change that impacts communities when it is directly at odds with the demands of the governance structure you’re working under. And therein lies the existential crisis of leadership.

I like the framing of it as an industrial complex; it really is set up for competition. Even if what communities need is more collaboration between organizations, the structure sets us up to be in resource and credit competition. It’s so counter-cultural that trying to change how these systems function burns you out.

In reading about them or talking to people in these roles, I have to say, I’m most excited about exploring co-leadership models. And I find they are all so different.

I am glad that as part of your work with Inspiring Communities over the next three months you will support us in considering a co-leadership pilot. I’m just really excited about the possibilities.

The reason I’m excited to be doing this work now is that after the pandemic lockdowns, people are recognizing that operating like everything is fine is no longer tolerable. When apathy becomes more uncomfortable than action, that’s when change happens. Hierarchies and binaries are becoming too uncomfortable for me to maintain so now I need to move through the discomfort and uncertainty of change. This works affects us all, and because of that, we have personal stakes. The success or failure of whatever change we implement will have a personal impact. I think it’s a good thing to have leaders that are motivated by having a stake in the impact of their work. There is more understanding and familiarity with the consequences of complacency.

I think at the same time, we need to really recognize that we can’t be personally responsible for all the failures when the system we’re working in has been failing us for generations. Even if it does have a personal impact on us, we need to separate our sense of self from failures that are beyond our control. Leaders are positioned in the hierarchy as the person ultimately responsible for all consequences of action or inaction, and dismantling or reducing that burden creates more breathing room to keep going.

When we see these larger issues we’re trying to address as a collective challenge, there’s so much more potential for change in collaboration, undermining the hierarchies putting us in competition with each other.

This is likely why Christian Bason says we need “a new kind of leadership that is not internally rooted in individual organizations but leads from a whole new perspective”.

It’s been really powerful to think of leadership beyond this lonely, isolated, winner-takes-all mountaintop with a pedestal on it. And also beyond a visionary or servant leader because I see that as kind of an anti-hero. But leadership as an ecosystem – something you actually can’t do alone. There’s a saying, “a three-stranded rope is not easily broken” and it’s because we are better and stronger together. It’s not just about lessening the harm, it’s also the mutual positive benefits of collaboration.

You can’t be breaking through glass ceilings and building trails that never existed before by yourself. You need people backing you up, laying the foundation and reinforcing it for other people to come through too. There are so many different types of leader and there’s an expectation to do everything well. Especially in racialized leadership, there’s articles about super tokens. There have been offers of advice and coaching, but what would really support me is collaborators to actually contribute to expanding capacity.

We’ve been forced to adopt hierarchical parliamentary governance methods with a singular leader and everyone falling into line behind them and it reminds me of geese migrating in V-formation… how the leader at the front has the hardest wind-breaking position to make it easier for each one behind them. But in reality, that leadership position rotates within the group so that one individual isn’t always at the front – because it’s exhausting and unsustainable.

There’s a real bootstrap mentality that you should be able to do anything you want to do if you just work hard enough and this rugged individualism we buy into actually separates us from each other to the benefit of people maintaining power. We take back our collective power when we recognize and support each other’s strengths, redistributing the labour so we can all benefit from everyone’s expertise.

I think my queer identities have really informed my approach to building alternative models. Working outside of the norms, there isn’t a pre-existing tested framework we can easily adopt, everything needs to be considered and negotiated. Rewriting relationship scripts is critical to both my interpersonal and professional relationship building. Trying to ask questions that may seem obvious because we assume the norms are understood prevents us from misunderstanding our expectations of each other later. Sometimes this process of negotiating can be really exhausting but I always have to remember that the scripts we’ve been using haven’t been working either.

This is how we’re building community and supporting each other in a radical new world, so we need to recognize and account for the fact that there will be mistakes and it’s uncomfortable.

Governance and Regenerative Structures

Louise: I know I wanted to touch at least a bit on how governance needs to catch up with the alternative models we have discussed above. Specifically boards.

Yes and I think it’s bigger than boards. I think of governance as a relationship agreement. These are the parameters and terms of engagement that we’ve mutually agreed on. And that agreement becomes the container that holds us together and it’s supposed to help support clarity and trust, not become a barrier to the important work. It’s a framework for how we’ve agreed to collaborate.

We’ve been functioning in a relationship contract derived from the colonial parliamentary systems and it’s become so familiar and standard that we assume it’s a legal requirement when it’s actually just a norm. That’s how we continue to perpetuate the systems, is in the assumption that because it’s been this way, that’s how it has to be.

Louise: I think you’re right that it extends beyond boards and into staff structures, into partnership agreements, conflict of interest policies and codes of conduct.

It extends into all of our relationship agreements and I think this particular hierarchy of boards creates a really criticism-focused dynamic. People assume that they already know how to be a board member because they’ve been on boards before, it’s the same thing I see in cis-heteronormative monogamous relationships where everyone assumes we’re all doing the same thing, have the same goals, and as a result there’s a lot of heartbreak. I think there’s also a fundamental challenge of trust-building in hierarchical power-over models. The Board assumes its role is to hold the Executive staff to a standard which isn’t even usually agreed upon by the group. It’s fundamentally set up for conflict between the leadership teams in an organization and doesn’t leave a lot of room for the collective imagination.

Boards are such an underutilized team in organizations. There’s so much strength in bringing together a broad set of skills, strengths, and perspectives, and then we put everyone in a wrestling ring set up for power struggles. The focus of a Board is often maintaining the systems and upholding standards.

There can be quite a bit of focus on “what does the policy say”; when the policy is what’s creating the issue and it needs to be revised because it’s no longer meeting the present needs. Defaulting to a tool that is not fit for a new purpose isn’t necessarily helpful. It’s why I was excited to take the Innovation Governance Program. I wanted to learn how people are doing things differently in other contexts. I want to know what haven’t we tried? What can we move forward with now? And most importantly, who’s willing to take on what parts of this initiative?

And I love what you said about the collective imagination because it’s really like, what is our shared vision as a group? How do we elevate this conversation instead of drilling it down to its parts and following outdated perspective(s)?

I think the biggest challenge for most organizations is a lack of a clear shared vision. There’s a genuine lack of clarity when we make assumptions based on the systems we’re familiar with.

People aren’t clear why they are doing this work and it results in a lot of unproductive conflict. When there is a clear vision, I think there’s also a lot of trust when people are in conflict, because even if we disagree on an approach, we understand that we are working together on the same goal.

Our organizations can’t remain stagnant. The needs of our communities are great and solutions need to be changing to adapt to new circumstances. Our governance models also need to be nimble while also making sure everyone is on the same page about our intentions. These agreements need to be revisited regularly and everyone needs to be made aware of them again and again.

I can appreciate what you are saying. I recently participated in a virtual presentation by the Co-CEO’s of ProInspire sharing about their experience with transitioning to co-leadership in 2020. It was a rich discussion that included and involved the board also moving to a co-leadership structure in very much that reflective modeling you are talking about. And I’d say this was possible (how the leaders, staff and board came up with a model that worked for them) by their acknowledging that the status quo leadership model was not in service to their shared goals and vision.

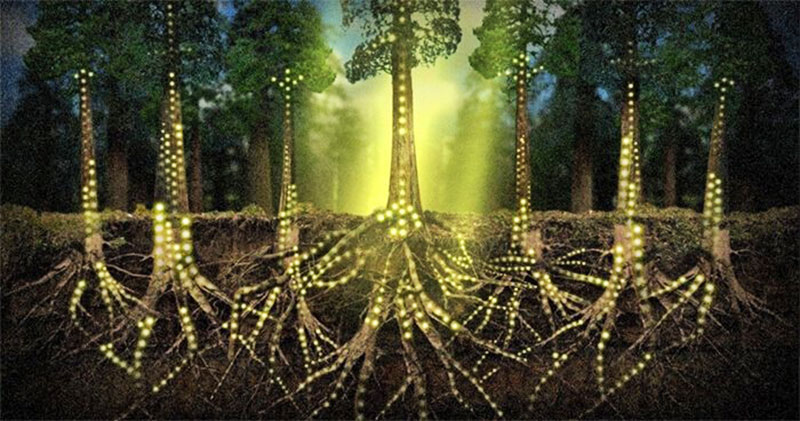

I’ve been trying to come up with a visual representation of collaborative leadership and at this moment because we’ve been functioning in an hourglass or sometimes diamond shape with a lot of hard edges and pinch points. How I envision collaborative leadership working well to solve the biggest problems we’re facing for our collective survival is the mycelium networks of fungi. These networks expand to their surroundings, connecting entire forest ecosystems and finding the most efficient paths to resource distribution.

Thanks Benny, this has been a great conversation. I learn so much getting out of my head and into a dialogue with you and with the readers.

And I am so very much looking forward to our last blog in this series which will hone in on your work to help boards and leaders in the sector with healthier transitions – now that you are a former nonprofit leader- smile.

I also wanted to share that, as I was listening to you speak I felt really open and expansive and generative and hopeful. When I looked up the word angst and found “angh”, I looked up the antonyms which were calm, ease, bliss, and joy. It embodies this need for ourselves and our sector to move from a rigid container to what is regenerative and reflective of how life and change happens.

For collective leadership we all need to figure out how we can work together efficiently to support everyone’s growth and ease. I believe that we can do this if we break down the rigid hierarchical structures and start trying new ways to be in relationship with each other. Collaborative leadership needs us to foster belonging and personal responsibility to the cause, moving away from the cult of personality singular leadership model towards a shared vision.

Three examples of co-leadership

The Council of Canadians – Co-leadership

Appointed two internal senior leaders as internal Co-Executive Directors when the ED went on a sudden leave. They were later confirmed as co-executive directors, in line with power sharing values of org, with specific minimum term.

The Bridgespan Group: Co-leadership models

3 Non-profits Share Their Approaches to Co-Leadership

A scan of the motivations, advantages and challenges of co-leadership. All slightly different models. Concludes with 3 tips: consider the interpersonal dynamic, don’t rush and don’t set the co-leadership structure in stone.

Sketch: Junior Executive Director

- A Triumphant Transition: New leadership for the next generation of Sketch

- Investment Readiness Case Study: Sketch Working Arts

Co-leadership as long-term succession planning. In a process designed to remove barriers and promote EDI, Sketch promoted a staff into a co-ED role, providing long-term training and onboarding while the retiring ED was still in place.

This is Part 2 of a series. Find the Intro and Part 1 here. Read Part 3 here.

Share this:

Comments are closed